When I tell someone about my research on cognitive labor inequality, their first question is often: how can couples fix it? I’ve developed some principles and strategies of my own, but if I sense that my questioner is looking for something more concrete—a full-fledged ~system~, say—I usually just refer them to Fair Play. It started as a book but has since blossomed into an empire of sorts, with an affiliated facilitator training program, documentary, policy institute, and much more.

To really boil it down, the FP system teaches couples to work through a deck of cards representing a huge array of household tasks: cleaning, calendar keeping, electronics & IT, gifts for family members, holiday cards, etc., etc. For each card, the couple designates one person as cardholder. That person then becomes responsible for planning, doing, or delegating whatever the card entails until the couple reallocates the deck (which the FP system suggests they do on a very regular basis).

I recommend Fair Play so often because it’s got several features that align quite well with what I’ve found in my own research. For one, the system’s creator, Eve Rodsky, argues that when couples are dividing labor, they often focus exclusively on execution (what I call physical labor) and neglect conception and planning (what I call cognitive labor). The FP system calls for an explicit division of all three task components. This is key!! If you are the “groceries” cardholder, you’re not doing your job if you physically go to the grocery store but rely on your partner to keep an eye on the pantry and track any staples you’re running low on.

Likewise, for each card, couples are supposed to work together to jointly establish a “minimum standard of care.” Take the “Meals (Weekday dinner)” card: establishing a minimum standard would mean agreeing on criteria like an appropriate timeframe for serving dinner (is 7pm too late?); what qualifies as nutritious (must there always be a vegetable?); and how often it’s okay to resort to takeout (is “every night” a reasonable answer?). One of the challenges I see couples running into over and over is that partners have very different ideas about a) whether something is worth doing in the first place, b) how often it needs to be done, and c) what constitutes good-enough. By hashing that out up front, you can minimize the number of times one partner declares a task done and the other finds fault with whatever they did. (Okay, yes, technically the laundry is washed and dried, but is it “done” if it’s not folded and put away?)

But while I recommend the FP system widely, and even cite it in my forthcoming book, I always worry a bit about hyping up an intervention that hasn’t been rigorously (at least by academic standards) tested. Sure, it makes sense, aligns with my research findings, and has been anecdotally heralded as a relationship helper…but where’s the hard data?

I was super pleased, then, to see that researchers at USC recently put out a report formally evaluating FP’s effects on measures of physical health, mental health, and relationship quality. The report details findings from one core study, implemented across two different cohorts (Cohort 1 - a group of parents who have been followed by the research team since 2020; Cohort 2 - a group of employees from a large, unnamed healthcare company).

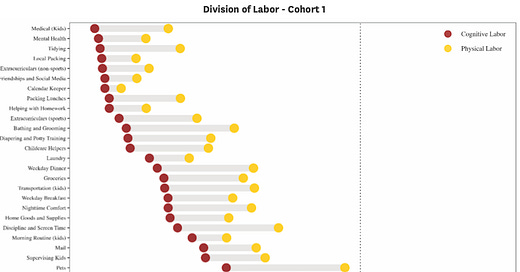

Both groups were invited to fill out an extensive (50-minute!) baseline survey measuring things like mental health, stress level, relationship quality, and division of household labor. For the latter, participants separately reported who was responsible for the planning and execution of 30 different task categories drawn from the FP card deck (using a 1 to 7 scale ranging from “all me” to “all partner”).

Those who completed the survey (and were eligible/interested)1 were invited to participate in an online version of the FP system, comprised of several modules and optional coaching with a Fair Play facilitator. Anyone who at least started the intervention was later asked to complete a follow-up survey that was basically identical to the baseline survey.

Before I describe the results, there are a couple caveats here: this is not peer-reviewed research (though it’s possible that is forthcoming). The evaluation was done “in coordination with the Fair Play Policy Institute.” A fully independent study would be ideal, but I didn’t see anything that made me question the integrity of the study or its conclusions. The sample is small and not representative of the population (it’s very female and skewed toward middle- and upper-middle-class respondents). Finally, because this is not a randomized controlled trial,2it’s hard to say for sure whether the changes reported are attributable to the intervention (i.e., using the FP system) or to some other factor. Still, I see all of the above as reasons to be cautious about extrapolating too far from these findings, but not cause for disregarding the study altogether. This is an incomplete, but intriguing, first step.

So, what did they find? Here are my three big takeaways:

1) Cognitive labor is really unequal, and that inequality is associated with a bunch of other bad things.

Okay, this one isn’t super surprising, but I’ll admit to finding it validating whenever quantitative research supports my qualitative findings. Respondents reported that women do a lot more planning and a lot more execution of household tasks, but the gender gaps were larger for cognitive than physical tasks. For every single one of the 30 task categories among cohort 1, and for 29 of the 30 among cohort 2, the cognitive component is closer to the “all female” end of the spectrum than the physical component is.

Greater levels of cognitive labor inequality were associated with lower relationship satisfaction, higher stress, more depressive symptoms, more symptoms of burnout, worse physical health, and worse mental health for women. Yikes!3

2) If you can get a couple to implement the FP system, good things tend to happen, albeit on a modest scale.

Respondents who completed the intervention (at least in one of the two cohorts4) got more equal in their labor allocation by the follow-up survey. The report includes figures but no numbers, so I’m eyeballing things here, but it looks like there were greater shifts post-intervention in cognitive than in physical labor. The size of the shift isn’t huge—still not even close to an equal split—but it’s something. (And it’s quite common that an intervention will have a small effect size, just given all the variation from person to person.)

Those who shifted their cognitive allocation more had fewer depressive symptoms and lower stress (in Cohort 1 – no significant change for Cohort 2) at follow-up; those who shifted their physical allocation more had better relationship functioning (Cohort 1 and Cohort 2) and lower levels of burnout (Cohort 2). Other outcomes weren’t significant.

3) But, it’s difficult to get someone to start the system, let alone complete it.

The researchers mention the challenge of sample size several times in the report, and I agree it’s a big one that likely interfered with their ability to see significant results. They invited 337 people to try the FP system, but only a bit over half (56%) of those folks actually started it and a bit over one-quarter (27%) made it all the way through. You might say, well, something is better than nothing—but as the authors note, the core of the system (i.e., the card game) isn’t introduced until module 5, which only about a third of participants completed!

Final thoughts:

We need more research! As I hinted above, I see this study as a first step rather than the final word. My hope is that follow-up work will include a much larger and more representative sample, incorporate more men’s perspectives, and function as a true RCT. I would also like to see a more robust qualitative component focused on how people are using the system—anecdotally, I hear about a lot of customization—and why they stop or fail to start. (Or, framed slightly differently, what kind of couples are the best candidates for an intervention like this one?) I have my suspicions about the drivers of the high attrition rate: the time commitment required, which might be overwhelming, especially for parents of young kids – paradoxically also the group that probably most needs an intervention like this one!; difficulty getting partner buy-in; the fact that this system doesn’t—and to be fair, probably can’t—address the broader structural and cultural factors that channel couples toward inequality in the first place. This study wasn’t set up to assess those questions, alas.

In the meantime, will I keep recommending the FP system? Yes. It’s not for everyone (as demonstrated by the high attrition rates), but if a couple tries it and likes it, this study suggests it could very well help move the needle on both cognitive labor inequality and individual/couple well-being. It’s also still the best low-cost tool I’ve seen for addressing labor inequality. Couples therapy might be effective, too, but it’s much more expensive and (at least for some people) carries a stigma that likely makes it a harder sell.

It’s a little unclear based on the report, but it seems that for Cohort 1, respondents had to complete the survey to be potentially eligible for the intervention; in Cohort 2, it seems anyone who started the survey was potentially eligible.

It appears that the researchers may have initially intended this to be an RCT: they randomized one of the cohorts into an intervention and a waitlist group. But the waitlist group was ultimately invited to complete the intervention, and as far as I could tell the reported results either included the combination of both groups’ outcomes or just focused on the intervention group’s outcomes, rather than comparing the two. My guess is they switched gears because of the small sample size.

Remember, these are associations; the researchers aren’t able to assess causality here. Also, they only heard from one member of each couple; it’s possible that the respondent’s partner might have a different understanding of their labor allocation.

They report that the labor allocation changes weren’t significant for Cohort 2.

I was so happy to read this dispatch, thank you so much for sharing! As a Professional Organizer specialized in Family Organization and Workplace Trainer specialized in Work-Life Balance via Organizational Skills, I refer to the FP Method quite frequently.

I find that game-ifying something that can often be a heavy process is a wonderful way to approach it in order to look at it with fresh eyes and enables people to be on the same team.

That being said, I find that one major drawback to really make invisible work visible is that there is only one card per activity. In other words, the card for weekday meals should actually be 5 cards vs the card for mowing the lawn that could actually be one card every two weeks.

The perception of equality could be skewed if we're trying to share the cards evenly. My ''stack'' could be the same size as my husband but if I hold many of these recurring activities cards that should be multiplied, I continue to do more work while my husband is under the impression that things are fairly distributed.

That being said, it's still the best solution I've found to make domestic mental load more tangible.

I really appreciate reading your thoughts Allison! Have a great day!