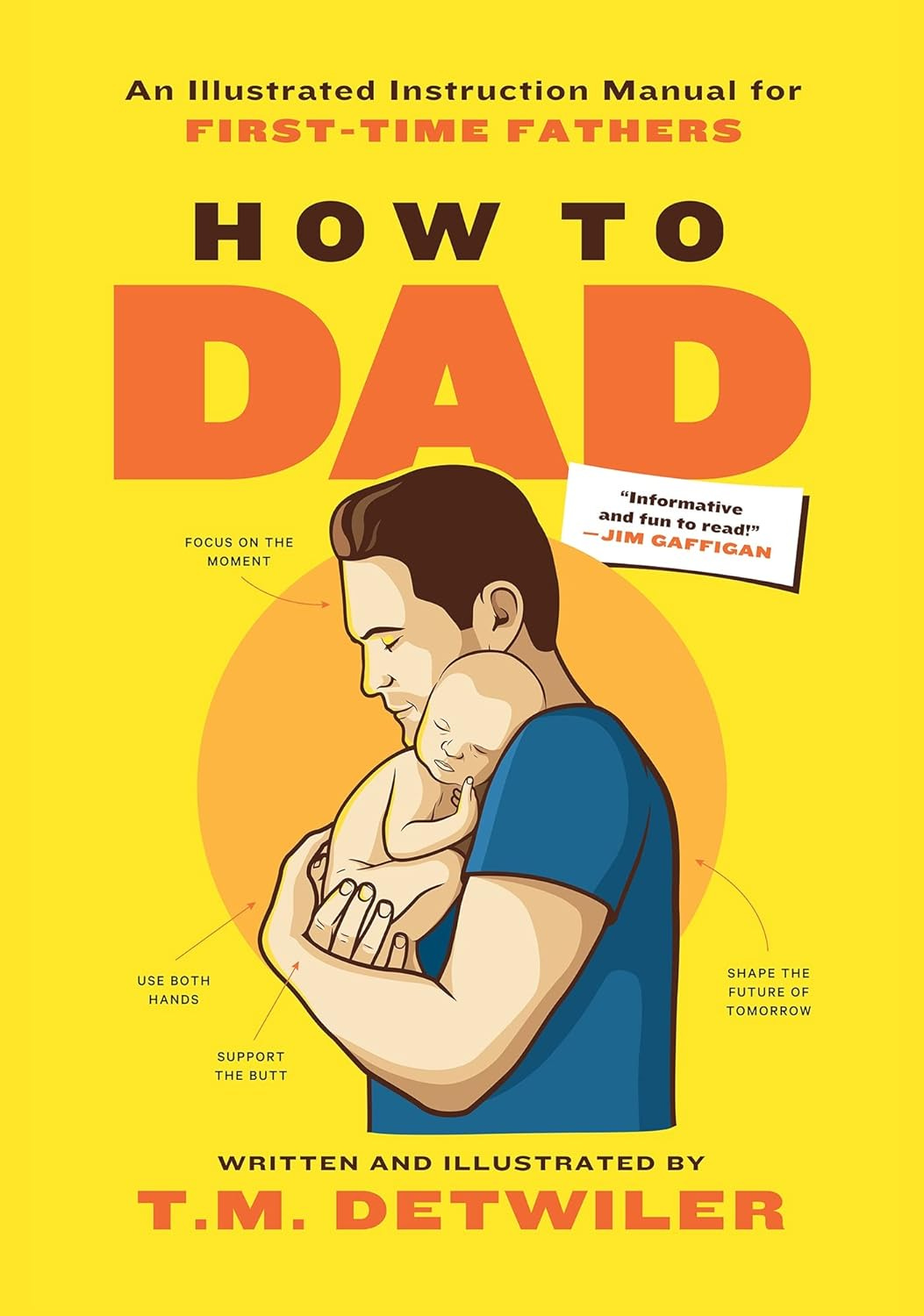

Lately my husband’s been starting many of his sentences with, “Well, the book says…” The book in question is usually The Expectant Father: The Ultimate Guide for Dads-to-be, or perhaps its sequel, The New Father: A Dad’s Guide to the First Year. He hasn’t yet begun his latest acquisition, How to Dad: An Illustrated Instruction Manual for First-Time Fathers, but I imagine I’ll be hearing about that one shortly.

These texts are part of a growing (I suspect, anyway, based on a recent bookstore perusal) subgenre of parenting books geared toward helping men understand pregnancy and learn to care for young kids. As Armin Brott, lead author of The Expectant Father (and The New Father) writes about his wife’s pregnancy with their first child, “There were literally hundreds of books and other resources designed to educate, encourage, support, and comfort women during their pregnancies…[but] there simply weren’t any resources for me to turn to.”

Granted, the 1st edition of Brott’s book came out in 1995; contemporary fathers-to-be have considerably more information at their disposal. But his broader point, that women’s experiences of pregnancy have been discussed far more thoroughly than men’s (or, to use less gendered language, birthing partners’ experiences have been more widely discussed than non-birthing partners’), still holds. Countless more words have been written about what I’m going through than what my husband is going through, and most existing resources assume a reader who is pregnant.

This pregnancy books gender gap is just one facet of a much broader issue: I have been subtly and not-so-subtly prepped for a primary caregiving role since I was a little kid; my husband, like many men, has not. Some of that training was formal, like the Red Cross babysitting course I took; more of it was informal and/or implicit, like the way I was encouraged to hold new baby cousins or taught to soothe my dolls. Later, “training” took the form of conversations I had with my friends, first speculating about what pregnancy and motherhood might be like, and more recently talking in great detail about their actual experiences with the whole thing.

My research—to say nothing of common sense—suggests the caregiving skills and knowledge gaps your average hetero couple enters parenthood with helps shape the gender inequality in parenting responsibility they (usually) later adopt. It would be sort of like if an accountant married a poet: who do you think would end up filing their taxes?

Books like Brott’s are not going to magically close the knowledge gap, but they can narrow it. And on a deeper level, they can help validate the idea that fathers—and all non-birthing partners—have a role to play, even in the pregnancy and newborn stages. (One might think this was obvious, but just a few weeks ago I was at a dinner with a 50-ish man who blithely recalled how there really wasn’t much for him to do, parenting-wise, until his kids were weaned.)

I could, and maybe should, stop there: yay, fathering books! Isn’t it great that they exist?! But, me being me, I also have some, er, suggestions for improvement and philosophical quandaries for reflection.

On the improvement front, some of these fathering resources seem to reinforce gender stereotypes even as they subvert them. How to Dad, for instance, contains full-page spreads on a) how to ride a motorcycle, b) how to know your beef cuts (because “as a dad, you might be expected to be the grillmaster-in-chief”), and c) how to split firewood and make a fire. I suppose these topics could be very generously described as parenting-adjacent—what if you and your newborn are stranded in the wilderness? But I read them as attempts to reassure readers that they can caregive and still be dudes. If that keeps men going through the chapters on infant sleep and diaper changing and when to introduce solids, I suppose the tradeoff is worth it?

More subtly, the fathering books occasionally pit men against women in ways I—admittedly not the target audience!—found off-putting. Like when Brott argues that “we, as a society, value motherhood more than fatherhood.” Really? Or when he instructs men to “stand your ground” when their partner asks them to do something differently: “Many women have been raised to believe that if they aren’t the primary caregiver, they’ve failed as mothers. In some cases, that leads the mother to act as a gatekeeper,1 not sharing in the parenting and actually limiting the dad’s involvement to an amount she feels isn’t a threat.”

Brott's correct that there are multiple “right” ways to burp a baby or put them to sleep. And he nicely alludes to the fact that women are much more likely to be held accountable for parenting outcomes than men, meaning their incentives (and related anxieties) are often different. Still, the advice for men to “stand your ground” in response strikes me as more antagonistic than necessary.

On a more philosophical note, perusing these books and talking them over with Eric has left me wrestling with some Hard Questions. I’ll throw them out here at the end, not because I’ve satisfactorily answered them but in hopes that talking openly about the struggle is helpful for others who’ve been through something similar. (Gender scholars, they’re just like us!)

In essence, I’m wondering what a commitment to equal partnership should, or could, look like during the pregnancy stage of parenthood. It is very clearly impossible for the physical part to be equal, so I’m mostly talking about the cognitive piece here: tasks like picking out an OB, assessing what constitutes an appropriate risk in exercise or diet (maybe cucumbers need to go?), deciding whether to get an epidural, and so on. These kinds of choices have the potential to impact both partners’ child, and thus should perhaps fall under the “joint parenting” rubric, but a disproportionate immediate effect on one partner’s day-to-day life and/or body.

How, then, should you weigh the risk of starting your parenting journey on unequal footing against the risk of reducing the birthing partner’s bodily autonomy? How should you weigh “book knowledge”—the only kind of pregnancy knowledge accessible to a cis man—against the “embodied knowledge” that arises from gestating new life? What’s a committed “my body, my choice” feminist and strong advocate for labor equality to do?

As I said, I’m in the thick of things right now and won’t even attempt to answer my own questions. If you’ve found a way to resolve similar tensions in your own life, I’d love to hear about it, whether in the comments or via email. (Hint: you can always hit reply to this post, and it’ll go to my inbox.) In the meantime, I’ll keep muddling through.

Three strategies I use to keep work from taking over my life

And now, for something completely different, I wanted to experiment with a little behind-the-scenes bonus for paid subscribers. One of the core challenges of academic life—slash writer life, slash freelancer life; heck, slash living-under-capitalism life—is figuring out how much work is enough. When no one is paying attention to whether or when you come into an office, when your “deliverables” and checkpoints are months or years apart, when there is always something more you could be doing to “build your brand” or advance your career, how do you keep moving forward and set reasonable boundaries that prevent work from taking over every waking minute?

There are, of course, many ways to do this, and I’d love to hear about what works for you. If you haven’t figured it out yet, here are three core practices that consistently help me.

1) When you’re working, work; when you’re relaxing, relax. Minimize the in-between.

Sometimes when I’m at a coffee shop or library, my attention drifts to the strangers working around me. (Okay, yes, I’m nosy.) Often, I end up marveling at the number of apps and tabs they’re toggling between: Word document to social media page to word doc to text message to random google search, etc. How, I wonder, does anything ever get done? When your attention is fragmented, everything takes at least 2.4 times as long. (This is a made-up number, but I stand by it.) The more you single-task, the more efficient you become, and the fewer hours you need to work.

2) Get to know your own personal diminishing-returns curve and learn to hop off at the right moment.

While it’s true there is always more you could be doing at any given time, now isn’t necessarily the right time to be doing it. Most evidence I’ve seen—coupled with first-hand experience—suggests that roughly four hours (preferably broken up into two or three chunks) a day of deep, focused work is about as much as a human brain can take before cognition and attention start to go downhill. When you feel the downward slide begin, pay attention. Unless you’re really up against a deadline, you’ll probably do a much better, faster job on whatever needs doing if you take a break and come back tomorrow. Though hustle culture may tell you something different, there really is no prize awarded for Most Hours Worked.

3) Master the art of weekly planning.

Half the battle, for me at least, is figuring out where to focus my limited cognitive energy and then holding myself (loosely) accountable to quitting at the right time. I do this by monitoring my focus in the moment (see point 2), but also via a regular planning session in which I a) brain dump all the tasks I need or want to get to in the week ahead, b) estimate how much time I think each will take (and then add buffer), and c) assign each task to a specific day and/or time. This method works much better for me than a to-do list because it forces me to prioritize (from the vast universe of possible tasks, what’s likely to be most impactful this week?); it helps me keep my expectations realistic (when I try to slot the six things I want to do on Wednesday in between meetings, I can clearly see that it’s literally impossible); and it makes me feel okay about quitting at a reasonable hour (maybe it’s only 4pm, but I finished everything my past self determined was “enough,” so it must be fine). Be forewarned: it takes a lot of trial and error to figure out how much is reasonable to pack into a week; I recommend leaving yourself a lot more buffer than you think you’ll need!

I’ve gathered these practices from a whole host of sources—many of which I’ve surely forgotten about—over the years, but I’ll give particular credit to Cal Newport, Oliver Burkeman, Robert Boice, and the NCFDD for relatively recent inspiration.

If this sort of thing is helpful and/or interesting, let me know in the comments or by replying to this newsletter, and I’m happy to go deeper on the above or explore related topics.

The concept of maternal gatekeeping was popularized by Allen and Hawkins in a 1999 paper that defines it as “a collection of beliefs and behaviors that ultimately inhibit a collaborative effort between men and women in family work by limiting men’s opportunities for learning and growing through caring for home and children.” Later work expands on the definition and sometimes includes facilitative as well as inhibitory actions, the latter of which Lee and Schoppe-Sullivan describe in a nice turn of phrase as “maternal gate opening.” I have some critiques of the gatekeeping concept, but I’ll save that for another venue.