When J.D. Vance’s comments about the “childless cat ladies” running our country resurfaced over the summer, they barely registered with me. I was entering the worst phase of my first trimester and plagued by constant nausea, hypotension that left me unable to walk more than a few feet without needing to sit down, and dehydration (stemming from the fact that EVEN WATER was difficult to stomach).

Suffice to say, I was not up for much in the way of trenchant sociological analysis. All I could muster was a lament along the lines of, “I wish I was still a childless (dog) lady!” Though, per Vance, I would not have a “direct stake” in the country’s future, I would at least be able to leave the couch and tolerate something more flavorful than a saltine cracker.

A few weeks later, thanks to large quantities of B6 and Unisom, my thoughts about Vance and his cat ladies grew slightly more sophisticated. First, I lamented the cruel irony: after wavering for years on the question of children, why did I have to make the leap toward parenthood just as the neopatriarchal arm of the Republican party was gaining prominence and shaming people who took the childfree path—a path I was *this close* to taking myself? “I am not with him!” I wanted to clarify. If anything, pregnancy has only solidified my commitment to reproductive freedom.

Second, I wished I was teaching my undergraduate class on family. Vance’s remarks would be the perfect tie-in to the lecture on reproduction! Since I’m not teaching that class this semester, I figured the next best thing would be to share with you a (modified, and much more politicized) version of what I might have said to my students.

Fertility rates have dropped

First, let me say—reluctantly—that Vance isn’t all wrong. To quote the great Whitney Houston, “the children are our future.” In a very literal sense, society depends on children, who grow into adults, who work and spend and in some cases fight on a nation’s behalf. If there are not enough of these future-productive-adults in the pipeline, problems occur.

Okay, but how many children count as “enough”? Demographers talk a lot about the “replacement fertility rate,” or the average number of children each woman needs to have in order to ensure steady-state population size: about 2.1.1

If the fertility rate drops below 2.1—and there is no immigration, a point I’ll get back to later, given this is Vance we’re talking about—then a society will shrink over the long term. More immediately, the age distribution of its populace will shift, getting more top-heavy. That’s problematic when you think about the way systems like Social Security are set up: workers pay into it while they are young and healthy enough to work, and they reap the benefits when they are older and retire. If the number of retirees outpaces the number of workers, the system starts to fall apart – as is already happening with the aging of the Boomers.

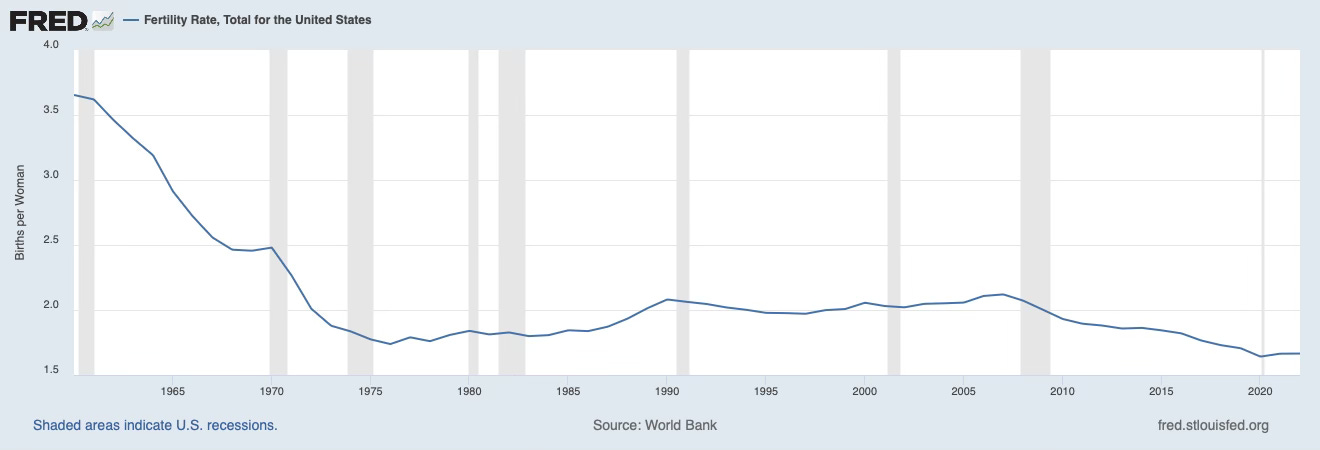

The U.S. is below replacement fertility, and has been for more than a decade. In 2007, the last recent high point, we were at about 2.1 kids per woman. We hit an all-time low of 1.6 in 2020, and things haven’t rebounded much since.2 All of that to say that Vance is correct to identify the rise of Americans having no kids (or just one kid) as a meaningful trend. And he’s also correct to identify this as an issue a smart government should concern itself with.

From there, though, Vance and I part ways pretty significantly. Both his diagnosis of the problem and his proposed solutions are misguided.

Why have fertility rates dropped?3

As far as I can tell, Vance would likely point to a decline in virtue, linked with Americans’ growing secularization. He famously converted to Catholicism in his mid-30s, less famously citing the work of St. Augustine as a major influence: “the best criticism of our modern age I’d ever read. A society oriented entirely towards consumption and pleasure, spurning duty and virtue.” Vance seems to assess the decision to remain childfree as a quintessential case of contemporary decadence: to forego parenting, for many in his camp, is to choose self-interest over society.

The idea that norms and values around family have shifted in recent decades is difficult to dispute. Surveys show a drop in the proportion of Americans who believe marriage is necessary, that a man or woman needs children in order to be fulfilled, and that a proper “family” consists of a married woman and man and their children. But is that decline and degradation, or is that…change?

One’s answer to this question is as much about personal belief systems and ethics as it is empirical data. (My own point me toward the “change” interpretation.) But on the empirics side of things, I will note that the “traditional” family Vance and co. like to reference was more a historical anomaly than an actual, long-term precedent from which we’ve departed, as the historian Stephanie Coontz’s work so nicely shows.

More importantly, I think the emphasis on norms change as primary driver of fertility declines misses the more important role played by structural changes. To his credit, Vance does sometimes acknowledge one such shift: raising kids is expensive, and lots of families lack the financial security to do it.

But there’s also a much more positive story line here, one which Vance overlooks: women have gotten more economic, educational, and reproductive freedom, and they’ve leveraged that freedom to make a wider range of choices about their family life. Globally, there’s an inverse correlation between women’s educational attainment and fertility rates. In countries with more-educated women, families tend to be smaller. The availability of hormonal and long-acting birth control, plus the increasing acceptance of women in the paid labor force, also coincided with declines in fertility rates over the last half-century or so.

More opportunities for women means more opportunity costs to having children. If you are in the throes of 24/7 “morning” sickness, or up all night with a colicky infant, or pumping breastmilk every few hours, it’s hard to keep your job or continue your degree. And it seems near impossible to continue working or studying at the same intensity.

Some women decide the costs of kids are never going to be worth it; others (it me!) opt to wait until they reach a certain level of professional security before entering motherhood. That often means they get started on the whole reproduction thing later in life, which in turn leaves them with less biological clock time in which to gestate more than one child.

I could keep going on the reasons-fertility-is-declining train,4 but I want to save space and energy for what is perhaps the biggest divergence between folks like Vance and folks like me.

What should we—society, and/or our government representatives—do about declining fertility?

Vance et al. want to roll back the clock on women’s reproductive rights, and they are having alarming success in this endeavor. They also seem to pine for a return to old-school gender roles (though this quieter part isn’t always said out loud): bring back manufacturing so men can earn higher wages and be better breadwinners; subsidize informal childcare so women can go back to nurturing.5

A far more promising approach is to invest in creating the conditions that make parenting—and mothering in particular—less expensive, less isolating, less exhausting, and less in conflict with continued participation in the paid workforce. Pass a national paid family leave bill. Subsidize high-quality early childcare, or better yet make it free for all. Incentivize men’s greater participation in childrearing.

And then step back and let people make their own choices about whether, and how many, children to have. Some of them will still, under any circumstances, choose the childfree life. Some will, under this more parenting-friendly regime, choose to have 3 or 4 kiddos. It's all okay!

Especially if you stop treating immigrants as an inferior class of people. Even as fertility rates have dropped below replacement rate, you may have noticed that the U.S. population has continued to grow, thanks to net immigration. If you are truly concerned about population decline, it makes no sense to be so anti-immigrant. Unless of course you also have ideas about the kind of people who make “desirable” Americans…

Thanks for all the support and well wishes in response to last week’s dispatch! I’ve loved hearing from you, and I’m humbled and grateful that many of you took the plunge to go paid. Next week’s post—about why, if not to counteract the decline of American virtue, I decided to pursue parenthood—will be for paid subscribers only. Oh, and if you haven’t yet taken the (very short) reader survey, it’s not too late!

It’s a little more than 2 because we assume not all children will make it to adulthood. And it focuses on women (and any trans/nonbinary folks who can get pregnant) rather than men in part because men/non-birthing parents are not always included on birth certificates and are generally less reliable sources when you ask them how many children they have.

As the headlines like to shout, this was a “historic low,” but not dramatically so: through much of the 1970s and 80s, we were in the 1.7-1.9 children/woman range. Also, in comparison to places like South Korea and Taiwan, both with 2024 fertility rates of 1.1, we are looking pretty good!

Answering this question would take me several books; plus, scholars are still trying to figure things out. Here I’m giving the Soc 101 answer – just know that if you’re interested in this sort of thing, the explanation here is just the iceberg’s tippy top.

E.g., another big part of the story is the decline in child mortality rates. If you can be reasonably confident most of your kids will make it to adulthood, you may feel less inclined to hedge your bets and have a lot of them.

Confusingly, at Tuesday’s debate Vance acknowledged some of the problems with the existing childcare system and suggested the federal government should be more involved. On this point, I’ll believe it when I see it. As Vance also said on Tuesday, Republicans have a lot to do to regain folks’ trust on these issues.