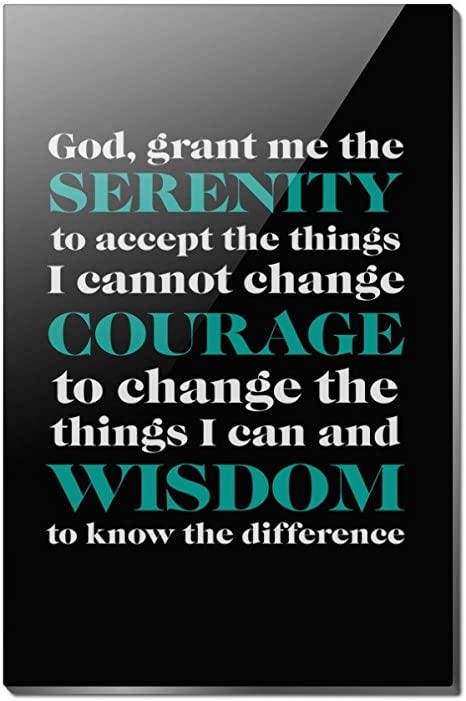

Growing up, a magnet printed with the Serenity Prayer was prominently affixed to my family’s fridge. You’ve probably read a version of this sentiment, originally written by the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr and later co-opted by such diverse constituencies as AA and (apparently) beleaguered mothers:

This magnet came to mind recently when I interviewed a woman named Daria about her household practices. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a reader of this newsletter, Daria is remarkably clear-eyed about where she and her husband Rob fall short of her egalitarian ideals vis-à-vis household labor. Rob, she explains, contributes to the physical labor side of the equation, but Daria does most of the cognitive labor for their household. As she awaits the birth of their second child this spring, Daria finds herself at a crossroads: should she choose serenity or courage? Accept cognitive labor inequality as her lot in life or push for change?

I found myself mentally replaying our conversation long after Daria and I got off the phone. It’s easy for scholars, journalists, and outside observers to paint in black and white: labor equality = good; labor inequality = bad. But as any therapist worth her salt will confirm, most of life exists in the gray. And I think this is particularly true when we examine “individual” problems that are actually system problems. Daria, like many women, is caught between rock and hard place as she wrestles with the inconsistencies of our gender moment—a time when ideas about what gender is and how it matters are changing rapidly, while most of our institutions (family, government, workplaces, etc.) uphold an earlier status quo. I hope her story helps you see your own in a new way.

The couple: Daria and Rob are a married couple in their early 30s with a toddler at home and another baby on the way. They spent the first part of COVID locked down in a tiny city apartment with an infant but have since decamped for more spacious quarters in the suburbs. Both spouses work full-time from home for companies in the tech/start-up space, Daria in marketing and Rob in product management. Their toddler goes to daycare 4 days a week, and on the fifth day Daria and Rob share supervisory responsibilities.

How they divide up household labor: Daria says the “doing” work (i.e., physical chores like cleaning, cooking, and home maintenance) is “fairly evenly split,” especially since their recent move. “Since we’ve owned our house, there’s more things that need to be done, in a way that’s actually balanced the load. We’re both pretty handy, but my husband feels more comfortable doing bigger project-y type stuff.” He replaced all their electrical outlets and switches, for instance, and is currently managing the project of getting solar panels installed on the roof.

However, the “thinking” work (i.e., cognitive chores like remembering what needs to happen when) falls heavily on Daria. She “manages all of the food coming and going from our house,” for instance, and is inevitably the one to notice when windows need cleaning or floors need vacuuming. Often, she’ll ask her husband for help tackling the task – whether by distracting their daughter while she cleans or by doing the cleaning himself.

This division – sharing physical labor but putting most of the cognitive work on the female partner’s plate – is incredibly common among the different-sex couples I’ve interviewed for my academic research. While the “drivers” of this unequal division are different for each couple, Daria’s story features several familiar motifs:

1) A traditional family model1 - Daria grew up with a stay-at-home mom and a dad who traveled often for work. “So naturally, I just sort of assumed that this is what household life looks like. I’m my mother’s child, so I just take things on and just do it, and nobody else is going to do it for me, so why would I expect that?”

2) Different thresholds – “[Rob and I] have different thresholds and expectations of what clean is, what’s acceptable.

It’s almost like he sees a certain line, and then I see at a certain line below that.

When I recognize something needs to be done, it’s just at the point where it’s getting to need to be done. He won’t see it until there’s food spread on the walls.”

3) Different meanings – For Daria, clutter and mess trigger the anxiety she’s long struggled with. “The fact that there’s dishes all over the kitchen and I can’t even make us dinner if I wanted to because there’s no space, it really crosses over into that emotional side.”

4) Different career paths – Daria’s current job is just that: a job. In fact, she says she’s never really found work that feels truly fulfilling. In her current role, “the fact that I don’t like my job, and I feel underpaid, it makes me feel like I don’t put as much energy into it. And my husband kind of feeds into that.” They rely on Daria’s income, but Rob makes more money and carries the health insurance and more generally leans into his career in a way Daria does not. And so it makes sense to both of them that she would be the leader at home.

What she’s working on: Daria is not wholly satisfied with her status as default cognitive laborer for the household. But the question of how to change—and whether it’s worth it, or even possible—is difficult to answer. She framed her options this way:

“There’s some reckoning that needs to happen. Or, I just need to own the fact that this will be my stress forever.”

As of now, Daria is leaning towards changing her own behaviors and expectations rather than pushing Rob to step up cognitively. She’s gotten good about asking him for help rather than doing everything herself, for instance. She recalled an epiphany a few years into their relationship: “I’m like, ‘Wait a minute, why do I have to do all this? We both work full-time.’” Since then, she’s learned that Rob is happy to help, “but I need to ask for that help.”

Regardless of whether Daria’s expectations (e.g., for cleanliness) are too high or Rob’s are too low, she says they’ve tried to meet “somewhere in the middle.” In practice, this often means that Rob talks her down when she’s feeling stressed: “When he sees me about to hit that breaking point, we’ll have a conversation about it, and I’ll say, ‘These are the things I need help with.’ And he’ll help me reprioritize to say, like, ‘This doesn’t have to get done. You want this to get done, and yes, we should get it done, but let’s push that off until this weekend, or I can take that on tomorrow.’”

Having their oldest child, Daria recalled, triggered a massive drop in her expectations, and thus something of a spousal detente. Parenthood “really resets everything about your life,” she explained. In the early days, “there would be weeks at a time where we always had clean laundry in a pile on the couch, because that’s as far as it made it. At that point, we both understood, like, this is just where we’re at, and we gave ourselves grace and space to figure this out as we go.” Once they moved past that hazy period, however, Daria’s expectations crept back up while her husband’s stayed put. These days, she thinks laundry should be put away in a timely fashion, whereas Rob “absolutely does not care if that gets done. It can sit in a laundry basket all week; we can have four loads of unfolded laundry and that’s never gonna bother him.”

Where they go from here: Daria is on the brink of two major life changes: having a second child and, potentially, making a big career move. She’s actively interviewing for new jobs that would take her down radically different paths. In one world, she becomes a freelancer and likely retains the flexibility and bandwidth needed to continue as cognitive labor point person. In another, she finally finds meaningful work, whether by transitioning to a more challenging role with direct reports or by joining a company whose mission she’s passionate about. She is optimistic that Rob would step up on the home front in that second scenario, because he’s done it before for short periods of time when she was recovering from childbirth or completing an intense certification program. What happens next, she says, “really just depends.”

I suspect that Daria’s choice between serenity and courage (to paraphrase my old magnet) will feel familiar to many of you. On the one hand, you may recognize household patterns that are, ahem, suboptimal. On the other, it may be hard to imagine devising a solution capable of overcoming the many factors that led you to where you are (upbringing, preferences, ways of seeing the world, etc.).

One path forward (courtesy of this article on how several family sociologists attempt to share chores) is to reframe the problem as a matter of you and your partner vs. “the system,” rather than you vs. your partner. In effect, it changes the question from “how do I get my partner to step up, and is it worth bothering?” to “how can the two of us find a better way of operating within the very real constraints posed by our incomplete gender revolution?”

If you’ve got a related story to share or a household labor dilemma you’d like help sorting through, comment here or send me an email, and I’ll do my best to respond.

To be clear, a traditional family model doesn’t always lead to traditional practices in adulthood! One of the research questions I’m working through at the moment is why and how some people end up pursuing remarkably different paths vis-a-vis gender norms than their parents did.

Is the difference in expectation about where the "line" is for household chores a systemic gender issue as well (men have lower expectations about when to clean than women) or a one off thing, assessed by every household? I also see myself in the "high threshold/low expectation" camp and always thought it was the burden of those who care more to handle it, but that doesn't bode well for household dynamics, I'd imagine. And around me it seems to alwways fall around the divide of gender, but is that really true?